A new school year often stirs up worries for Brooklyn parents. But just before public schools reopened earlier this month, parents and education advocates were already concerned about how to fund after-school programs at several schools across the borough.

After the state Office of Children and Family Services changed funding criteria for after-school programs last year, many Brooklyn schools — especially in southern neighborhoods — no longer qualified for support. That left parents and schools scrambling to figure out what to do with children after dismissal without paying thousands for private programs.

The same problem has emerged again this year. Several schools did not receive funding and are struggling to provide options for parents who work full time. City money is available in some cases, and parents can apply for assistance to cover after-school activities. At the federal level, advocates are also watching the U.S. Senate, where upcoming budget and legislative decisions could affect program funding.

For now, it’s clear the city and state are still adjusting to changes brought by the creation of LEAPs, though some argue the adjustments fall short. And for many Brooklyn families, the funding fight appears far from over.

Feeling the affects

The branch of OFCS that oversees after-school funding is the Learning Enrichment After-School Program Support initiative, known as LEAPs. The program funds activities across New York state, with high-need areas prioritized. According to OCFS, New York City received 42% of the total funding; Brooklyn programs received 17 awards totaling $20.2 million.

Community-based organizations apply for grants through what OCFS describes as a highly competitive online process. Applicants most likely to receive funding must show they serve a high-needs district, with at least half of students classified as economically disadvantaged. But even if schools meet the criteria, money may not be available. Programs are then placed on a kind of waitlist until more funds are released.

Without support, families are left to cover the cost themselves. That can mean as much as $3,500 per child for a school year.

Jill Levinson’s daughter used to attend NIA Community Services Network’s program at P.S. 185 in Bay Ridge. Now, she said, it appears there will be nothing.

Levinson noted that out of 581 students last year, 263 were considered economically disadvantaged — making $3,500 per child impossible for many families. Many parents cannot leave work early or work from home, she said.

Sarah Cooley, a parent at P.S. 104, also serves as the school’s Title I chair and a PTA member. She said the PTA has been brainstorming ways to help families afford after-school programs or find safe options for children once classes end.

“There’s talk of communal babysitters where one person looks after four or five kids,” Cooley said. “A tutoring center just closed, so there’s no real alternative. If families sign up early for NIA they get $200 less. But this is a big problem. The majority have both parents with jobs.”

Community Education Council (CEC) 20 member Kelly Clancy has children at Brooklyn School of Inquiry and P.S. 682 The Academy of Talented Scholars, which shares NIA’s program. But with no funding, she said she would need to pay $11,000 for all three of her children to attend — or leave them home, as she did last year.

Clancy explored the nearby Jewish Community Center, which provides school pickup, but said its fees were higher than $11,000. She also pointed out that with Brooklyn School of Inquiry being a Title I school, free programs should be available.

“One of the things that I’ve made it sort of my priority to do is to try to understand why other schools have access to free NIA programs and ours are paid,” Clancy said. “And I’ve never been able to get a satisfactory answer to that, especially because as of last year, we’re a Title I school, and we’re a NEST school. Like there’s lots of reasons why parents should have access to excellent, free after-school care for their kids, and we just don’t have access to it.”

John Ricottone, president of CEC 20, has again been pushing for fully funded programs across the district while questioning why LEAPs does not have enough money to meet demand.

“Times are hard,” he said. “It’s concerning when you can’t even afford a certain food, and then you have to pay $3,000 for one child. And imagine two children, or three children … it’s just the thought process is very concerning that people can’t even afford meals. New York State should be supplying that, especially with summer and after-school programs. This is a necessity. It’s not something that we get to put on the back burner and say, Oh, they don’t need it. They need it.”

Getting proactive

Annette Velez, executive director of NIA, said two District 20 schools that partner with the organization — P.S. 104 and P.S. 185 — did not receive funds last year and were again left out this year. The schools are on the “approved but not funded” list, and so far, Velez said, she has not heard any updates.

Still, NIA is preparing for future opportunities. Velez said the Department of Youth and Community Development will issue a request for proposals this fall for COMPASS after-school programs. COMPASS — short for Comprehensive After-School System of NYC — provides free activities for students in grades K-12 across the city. Once applications open, she said, NIA will apply for the 2026-27 school year.

“This funding stream happens to be more generous than LEAPS funding,” she said. “And offers opportunities for things like on-site services on some school holidays and the potential for summer programming. The vast majority of NIA’s programs are DYCD-funded, and we see this new [Request for Proposal] as a tremendous opportunity for reliable, long-term programming if awarded.”

In District 21, CEC 21 President Jay Brown is also pushing to secure money for several schools, some of which were unfunded last year. A handful received one-time support from Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office, but that aid has not been renewed. Brown said district leaders are now looking to the city’s $331 million expansion for Mayor Eric Adams’ “After-School for All” initiative, approved in June as part of the executive budget.

“We’re anticipating maybe three schools that were previously shut out will get funded through the new citywide funding expansion,” Brown said. “So that’s what we’re expecting, but we haven’t gotten that officially announced. We’re expecting it soon, so we’re hopeful. And then we have another one or two schools that they’re trying to figure out how to maybe squeeze some money out of that to their community schools, so they’re trying to figure out how to get some funding from the city expansion for them.”

In July, Adams and DYCD Commissioner Keith Howard announced that 40 after-school sites across the city will provide free seats. In Brooklyn, that included nine public schools and one charter school. Three are in District 21 — P.S. 101, P.S. 128 and P.S. 204 — while two are in District 20: P.S. 160 and P.S. 176. Although DYCD partners with the state, the LEAPs program is not administered by DYCD.

According to DYCD spokesman Mark Zustovich, 20,000 seats citywide were selected for the first expansion using criteria that will also guide future sites.

“The absence of existing COMPASS elementary programs,” Zustovich said, listing the criteria in a statement. “Economic need, and service gaps in those communities. 5,000 seats will open [in September], with the next rounds scheduled for the 2026-2027 and 2027-2028 school years.”

The remaining 15,000 seats will come from COMPASS elementary programs.

Future funds on the edge

Although new funding streams are being pursued, many programs remain without support — and some may soon lose their usual sources. One example is the federally funded 21st Century Community Learning Center program, which supports after-school and summer activities.

In early July, President Trump froze 21CCLC funding, sparking nationwide outcry. A couple of weeks later, he reversed the decision.

But that doesn’t mean the problem is solved, said Jenn O’Connor, a board member at the New York State Network for Youth Success. She is working to preserve funding by emphasizing the importance of after-school programs to federal and state leaders.

She explained that Trump wants to eliminate 21CCLC and redirect its money into a new block grant. If Congress leaves 21CCLC out of the fiscal 2026 budget, she said, the impact would ripple down to New York’s LEAPs program for the 2026-27 school year.

“Congress will take up the Trump administration’s proposed budget in September and mark it up,” O’Connor said. “The work that we’re doing now is to reach out to members of Congress and say, ‘Look, thank you for saving it. We hope you’ll save it again.’”

Afterschool Alliance, which advocates for affordable after-school access nationwide, reported that as of July 31 the Senate Appropriations Committee was pushing back against Trump’s proposal and aiming to keep 21CCLC at $1.329 billion — the same level as the fiscal 2025 budget.

“We’re just doing the education now to say to folks, ‘Bullet dodged, but it’s coming up again,’” O’Connor said. “Because if there are cuts to 21st Century or just the elimination of funds, those will impact the New York State LEAPs grantees. We are preparing for next year.”

DYCD spokesman Zustovich said the agency closely monitors federal developments to assess how they could affect young New Yorkers. CEC 21’s Jay Brown is also tracking the issue, as is Good Shepherd Services, which runs free youth programs across the city, including some in Brooklyn. While most of its sites receive 21CCLC funds after LEAPs, two of its community schools rely directly on 21CCLC.

Francisco Ochoa, a publicist at SKDK representing Good Shepherd Services, called July’s release of funds good news but warned the fight isn’t over.

“We will have to wait and see what the U.S. House of Reps decides to do,” Ochoa told Brooklyn Paper, noting that Good Shepherd is part of the New York State Network for Youth Success and has been strategizing with other 21CCLC recipients to ensure New York’s congressional delegation understands the program’s statewide impact.

Also keeping watch is Debra Sue Lorenzen, director of youth and education at St. Nicks Alliance. The North Brooklyn nonprofit runs programs at several schools with funding from both 21CCLC and AmeriCorps. The latter supports nearly 1,000 older students with college and career readiness, while 21CCLC helps serve about 600 disadvantaged students directly and another 4,000 indirectly.

“Their full goal is to help make our world a little bit better, help make our societies function a little bit better,” Lorenzen said of AmeriCorps. “And it’s a very, very modest amount of money, like a teeny amount of money that the federal government invests. But the return on investment is huge, and without that, we would not be able to provide those services, period, end of story. The funding doesn’t come from anywhere else.”

If 21CCLC is cut or eliminated, Lorenzen said, St. Nicks Alliance would face staff and service reductions, with ripple effects on the wider community. The nonprofit is now involved in advocacy through groups such as the Network for Youth Success and United Neighborhood Houses. Philanthropic donations are not a fallback, she said, because the community cannot fill the gap if federal funding disappears.

“The federal government has seen fit to make investments in these things for decades,” Lorenzen said. “Because they work, because the return on the investment of the public tax dollar is enormous, and that’s why they have been successful for so long.”

Reaching out to electeds

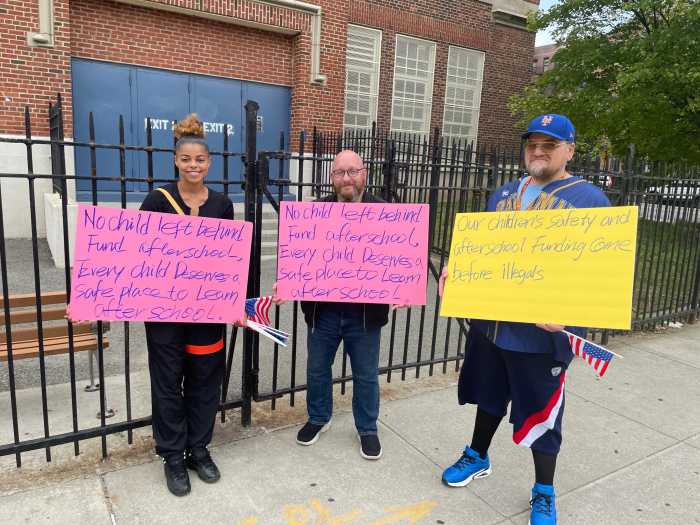

Some parent advocates have reached out to elected officials with mixed results.

While some politicians have been unable to provide assistance, others have taken action. One of the more significant efforts came in the form of a letter to Gov. Hochul, signed by Congress Member Nicole Malliotakis, State Sen. Stephen Chan, and Assembly Members Michael Tannousis and Alec Brook-Krasny. The letter urged the governor to restore funding for four D20 schools, including P.S. 104 and P.S. 185.

“The cumulative need across these schools totals approximately $800,000,” the letter reads. “This sum is well beyond what can realistically be raised through community fundraising. The afterschool programs at these schools, including those supported through the LEAPS initiative, are not supplementary services; they are essential and provide our students with safe environments, academic reinforcement, and cultural enrichment. Removing them disproportionately impacts working families, English language learners, and students from low-income households.”

OCFS Commissioner Damia Harris-Madden responded Monday, Sept. 8, noting that other funding sources exist beyond LEAPs, such as 21CCLC, COMPASS and DYCD programs. She also highlighted the state’s investments in each organization and referenced the Child Care Assistance Program, through which parents can apply for child care, including after-school services.

When Brooklyn Paper contacted the governor’s office about the letter, the inquiry was forwarded to OCFS’s press secretary, who provided comment but did not address the letter directly.

“LEAPS provides a safe and enriching environment for kids across the state of New York. We will continue to work with our state, city, and community partners to maximize afterschool access statewide,” the rep said.

Still, not everyone is optimistic. Many schools remain without funding, forcing parents to cover after-school costs themselves. Additional free seats through COMPASS elementary programs will not be available until the next school year. PTAs are scrambling to raise money or find alternatives for families who cannot afford to pay thousands, while attention also remains on U.S. Congress.

“That scares me the most,” said Cooley. “Working in education or youth programs, any bill there is, they should be scared. Of course, we should be scared too.”

O’Connor said she hopes Hochul will allocate more funding for LEAPs in the state executive budget. The time to act, she said, is now, as work on the next budget begins in January.

CEC20 recently posted information about the state’s Child Care Assistance Program on its website. But for schools in D20 without free after-school programs, CEC20 President Ricottone said he will continue to push for change.

“I’m not going to stop,” he said. “It’s a need. It’s a need for our children and the families. So I’m not going to stop.”