A young girl with autism, a sibling to two brothers on the spectrum, and two parents of children with disabilities share their unique perspectives on what the future will be like for their loves ones with special needs.

Letter To The World: A Child’s Pronouncement

By Emma Zurcher-Long I want to tell you that I am capable. Daring massively, eager to prove my intelligence, I will work tirelessly so that autistic children younger than me won’t be doubted the way I am. Pleading to the world, I ask that those who are not able to restrain their doubts, at least not mute voices like mine. Deciding stupidity bolsters egos while crushing lives with angry words disguised as kindness. They say hope is cruel for the hopeless, but maybe they are the cruel ones. Emma Zurcher-Long is 12 years old. She recently wrote, “My mind talks heavy thoughts, but my mouth talks silliness.” Emma writes by pointing to letters on a letter board and wishes people would “listen to my writing voice, but they listen to my talking voice instead.” Emma, who lives with her family in New York City, says her written words reflect what she intends to say better than when she attempts to speak. Emma’s Hope Book is the blog her mom, Ariane Zurcher, began many years ago reflecting what she thought was true; it is now where Emma publishes her short stories, insights, and opinions, particularly about autism. Emma’s writing has changed everything her parents once believed and were told. |

On Getting Out of the DrivewayBy Ellen Seidman

It makes me wonder whether Max will be able to drive when he grows up. I usually try not to let my brain fast-forward into the future, given that it’s not something I can control. Focusing on the here-and-now reality of Max is the best way to live life; as I learned when he was little, will-he-be-able-do-that musing causes a lot of anxiety. But the driving daydream is innocuous enough to indulge in, given that it’s not a major life necessity. My mom never did learn to drive, and it’s never been an issue. Some of my friends might say I never really learned to drive either, though I do. First I Google “adaptive driving specialist” because it’s always comforting to know about experts out there. Seems like there are “driver rehabilitation specialists” who train people in adaptive driving and outfit cars with special equipment. So, Max can someday add “driving therapy” to his already impressive list of therapies. Wonder if insurance will reimburse for that? Bwaaaaa-ha-ha-ha-ha!!! Then I Google “driving with cerebral palsy” and get sucked into comments in some forums. Some people with mild CP drive, but many with the more involved kind don’t. I picture Max pedaling his tricycle up and down our street and how much his control has improved over the years; this spring, he rode bumper cars alone for the first time. Then I ponder the intricacies of driving and wonder how he’d handle them with his fine-motor challenges. And how could he take the written test? Would they let him use his iPad? (This is what happens when my mind gets going.) Then I think about how years ago Max wasn’t capable of any steering at all, and I wonder just how much his skills will improve in the years to come. I find a YouTube video of a beautiful girl with right side hemiplegia who has adaptations in her car that enable her to drive using her left hand and left foot. Max’s CP affects both sides, but his left side is the stronger one so this gives me hope. It also occurs to me that if nothing else, maybe he could find some cute chick to drive him around. And then, DOH!, I search for “driverless car,” the one Google founder Sergey Brin tools around in. It’s an adaptive Toyota Prius that has laser-guided mapping, radars in the front and rear to determine positions of distant objects, a camera mounted near the rear-view mirror to detect traffic lights and moving obstacles like pedestrians and bicyclists, and other auto-features. The cars will hit California streets by 2015 and data shows they are smoother, safer drivers than people. Technology will be the answer for Max, I suspect, as the iPad and Proloquo2Go speech app have been for his communication. Although having a babe drive him around would be a fine option, too. The above is reprinted by permission of Ellen Seidman, a mother of two including 11-year-old Max, who has cerebral palsy, from her award-winning, inspiring blog Love That Max, where she writes about dreams, small accomplishments, special needs news, and all manner of struggles and joys relating to being Max’s parent, advocate, and champion. |

On Brothers, Hope, and StrivingBy Matthew D. Corsino Being the older brother of two siblings on the autism spectrum has never been an easy journey, but walking down this road with my brothers has given me the will to carry on no matter the odds. I didn’t really understand what autism is until I was about 9 years old, when my mother began to worry about how my brothers were not meeting their milestones. One day my mom explained to me that my brothers are children with special needs, and they were going to need a lot more help from us. After hearing that, I told myself, “No matter what, I will be the best older sibling—and stay strong, just like my mom.” During my years at Mercy College, I had the wonderful opportunity to intern and shadow occupational therapists through the OT assistant program. During clinicals I interned at Constellation Health Services in Stamford, CT, where I was able to work in both mainstream and mixed classes that contained typically developing children and children with special needs. I came to better understand how each child is different and has different needs. While spending time with my brothers at home, I began to think about how their needs will change as they get older. My brothers are 13 and 14 years old, and I began to wonder what would happen if they didn’t receive the services and assistance they have now—how would they be able to function, what would their communication skills be like? As a future occupational therapist, one of the most important issues, from my perspective—other than showing unconditional love and patience—is that families need to take more of an active role in helping their children reach their highest level of function when it comes to their independence. I feel this issue is so critical because, in the event that children do not have family to assist them, it may be extremely difficult for them to reach out for help when they need it most, depending on their condition. My mother has always inspired me and nurtured how strongly I feel about this notion. I have watched her from a distance over the years as she fought to ensure my brothers received every type of service that would benefit them, from speech therapy to a community habilitation specialist who came to our home to instruct my brothers on activities of daily living such as bathing, dressing, preparing their meals, and taking the bus. I have two major goals as a future OT practitioner. The first is to try to incorporate musical theory techniques into my treatment plans when working with children who have fine motor skills deficits. I have been playing guitar since I was 12, and during my schooling it dawned on me that playing involves a lot of fine motor skills that could be beneficial to kids who are lacking. My second goal is to help children function to their fullest potential, so that when they are adults they can be as independent as possible. I believe that this goal should be within reach not only for my brothers, but for all children with special needs—because no one knows what the future holds. Matthew D. Corsino is 21 and lives at home in the Bronx with his parents and siblings Stephen, 14, and Alexander, 13, who both have autism. He is currently studying to take his COTA licensing certification and continuing his studies beyond his associate’s degree to become an OTR (Occupational Therapist – Registered). |

On the Value of a PersonBy George Estrich

I knew nothing about Down syndrome except that it was bad, and that it meant Laura was different from me. I no longer believe the first—Down syndrome is simply Laura’s way of being human. As for the second: Laura is different, but the differences are superficial. This may seem an odd assertion, since the extra chromosome pervades her, and its effects texture our days. And yet these altered forms, eye and face and word, have come to contain and absorb what I know of love. Or love learned to alter itself, to accommodate the forms. She is no less my daughter, no less a person, for having an extra chromosome. Laura’s chromosome count taught me that every child is a genetic risk; her heart defect taught me that the risk is mortal; and years later, remembering an infant I did not know, I learn—again—that it is not only the chromosome, but our response to it, that shapes the contours of a life. Every tube, every wire, the violent nurture of surgery and the gentler nurture of feeding therapy, all working towards the clear pronunciation of a word: These hinged on the belief that her life was worth saving in the first place, then nurturing to its fullest potential. Everything we have done—teaching her to eat, to speak, every act of ambassadorship and interpretation—presumes the uncomplicated belief that her life is radically, democratically valuable. George Estreich received his MFA in poetry from Cornell University and is the author of the 2012 book The Shape of the Eye (Tarcher/Penguin), which Kirkus called “a poignantly eloquent meditation on the genetics of belonging” and from which the above is quoted with permission of the publisher. Last year our reviewer said: “This book will linger with you long after reading, and you’ll be glad it did.” |

Also See:

Find more articles for parents of children with special needs at nyspecialparent.com.

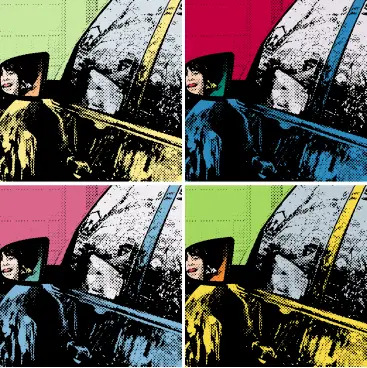

Max likes to sit in our car while it’s parked in the driveway and make like he’s driving. He grips the steering wheel, bounces up and down as if he’s on a bumpy road, and pretends to honk the horn. Dave or I hang outside, drink a cup of coffee and check email, occasionally noting “Watch out for that truck!” or “Hey, let’s go to the drive-in movie!” or “Don’t go too fast or the police will catch you!” (which cracks up Max every time).

Max likes to sit in our car while it’s parked in the driveway and make like he’s driving. He grips the steering wheel, bounces up and down as if he’s on a bumpy road, and pretends to honk the horn. Dave or I hang outside, drink a cup of coffee and check email, occasionally noting “Watch out for that truck!” or “Hey, let’s go to the drive-in movie!” or “Don’t go too fast or the police will catch you!” (which cracks up Max every time).