Why adults—not children—must lead uncomfortable conversations about boundaries, trust, and safety to stop child sexual abuse before it starts.

A family member once crawled into my 5-year-old’s bed when I wasn’t home to read her a book. The babysitter called me because she didn’t know what to do. I asked her to put him on the phone. I said, “Go home, please. We can talk about this tomorrow.” He was defensive, and the next day came in offended that I didn’t trust him. I said, “Do you want my daughter to grow up with vague memories of you crawling into her bed, and wondering what you were doing there?”

He saw my point. I said, “I am protecting you as much as anyone. You need to learn appropriate boundaries with children. Since you have no children, I will help you learn them”. To this day, he thanks me for making him aware of these boundaries and the importance of communicating them, especially now that he has children of his own.

As children, many of us were told not to talk to strangers, say no to unwanted touch, and tell a trusted adult if something feels off. These messages are not wrong, but they place too much responsibility on children to manage situations they are not developmentally equipped to handle.

Children rely on adults to set boundaries, interpret risk, and intervene when necessary. They often lack the language to describe subtle boundary crossings, especially when behaviors are confusing, normalized, or wrapped in affection. More often than not, adults are alerted to a problem not by a clear disclosure, but by something quieter: a moment of discomfort, a pattern that doesn’t sit right, a shift in a child’s behavior, or an interaction that lingers in the mind long after it’s over.

Psst… Check Out Starting Conversations on Domestic Violence: Advice and Tips from Experts

Why Speaking Up Is Hard

The vast majority (93%) of child sexual abuse does not involve strangers. It happens within families, schools, faith communities, and sports programs, often by someone a child, and the adults around them, knows and trusts. This reality requires a different approach to prevention. One that can feel awkward, destabilizing, and frightening.

Teaching children about body safety, consent, and speaking up is important, but no amount of education can turn a child into their own safety system. Prevention fails not because adults don’t care, but because three very human barriers stop us from acting.

First, it is genuinely hard to accept that someone we know or even love and respect could be unsafe with a child. We simply don’t see the behavior that might alert us to a problem, even if in hindsight it appears as an obvious red flag. We tell ourselves the behavior is harmless, misunderstood, or that we’re overreacting.

Second, even when concern lingers, many adults don’t know how to address it. Naming a boundary crossing can feel like lighting a match near a valued relationship. The fear of being wrong, causing harm, or losing a relationship can outweigh the risk we’re sensing. Silence feels easier. Sometimes we speak up once, receive an apology, and then never return to the conversation, hoping that was enough. Sometimes it is, often it is not.

Third, when someone does get up the courage to speak out, they are often met with disregard rather than support. Families and communities tend to circle the wagons, especially when concern is raised about a beloved person. The adult who speaks up may be seen as dramatic, disloyal, or disruptive. Without allies, intervening can feel lonely and costly.

So how do we overcome these obstacles to protect our children? As a survivor and someone who has worked to heal families from child sexual abuse for decades, here is my advice:

Watch for Softening Boundaries

Prevention isn’t about identifying “bad people.” It’s about recognizing conditions where harm becomes more likely.

Sexual harm rarely begins with a single overt act. It often involves a gradual softening of boundaries and an increase in access and privacy. This can include choosing to spend a disproportionate time with children rather than adults, unnecessary physical contact like tickling or wrestling, seeking privacy without a clear reason, or positioning oneself as the child’s special confidant.

None of these behaviors proves intent. But they are signals that boundaries may need to be firmed up immediately. Clear expectations, shared supervision, and early conversations can interrupt patterns before harm occurs.

Speak About Safety, Rather than Accusing

Intervention doesn’t require certainty. It requires courage and framing.

Addressing boundary concerns through a shared value—we all want children to be safe—keeps the focus where it belongs. Instead of speculating about intent or waiting for “proof”, we can name observed behavior and its potential impact.

This might sound like: “I know you care about kids, and I want us to be really clear about boundaries,” or “This isn’t an accusation. I just want to talk about what helps children build a good sense of boundaries.”

When adults learn to intervene in ways that align with the person they’re speaking to, conversations are more likely to lead to reflection rather than defensiveness. Intervention becomes an invitation to adjust behavior, not a verdict on someone’s character.

Do the Internal Work That Makes Intervention Easier

One of the least discussed aspects of prevention is the internal work adults bring to it.

Many adults carry unexamined experiences related to boundaries, sexuality, or past harm. Some grew up in environments where harmful behaviors were normalized. Others learned that staying quiet was the price of belonging. These histories don’t make someone unsafe, but they can make it much harder to notice or name discomfort in the present.

Doing our own work helps us tolerate complexity. It allows us to hold the reality that someone can struggle with boundaries without being cast immediately as a monster. Adults who can sit with that discomfort are far more able to intervene early and speak in ways that invite accountability rather than denial.

Build Safer Cultures, Together

Prevention is not a single conversation. It is a culture.

Safer communities are built when adults talk openly with one another about boundaries before something happens. We can name expectations around supervision, privacy, and care. Yes, this can be awkward and uncomfortable, but by seizing on these teachable moments and having conversations before harm occurs, it’s easier to share the responsibility of keeping children safe.

If you suspect a child may be experiencing sexual abuse, it’s important to reach out for support as soon as possible. You can contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline (1-800-4-A-CHILD / 1-800-422-4453) or chat at childhelphotline.org for confidential guidance. Trained counselors are available 24/7 to help you think through what you’re noticing and what steps to take next.

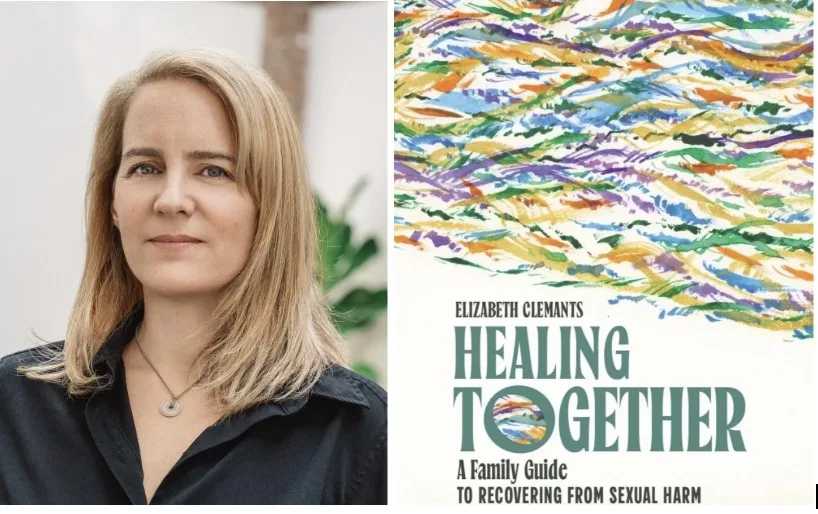

Elizabeth Clemants is the Founder and Executive Director of Hidden Water, a nonprofit dedicated to helping families heal from and prevent child sexual abuse, the author of Healing Together: A Family Guide to Recovering From Sexual Harm, and a New York City mother of three. She attended Columbia University School of Social Work, where she graduated with a Master’s in Social Work and a Minor in Law.

Psst… Check Out What Parents Need to Know About Sex Offenders in NYC