A new HBO film from an Academy Award-winning team puts the spotlight on an often misunderstood learning disability.

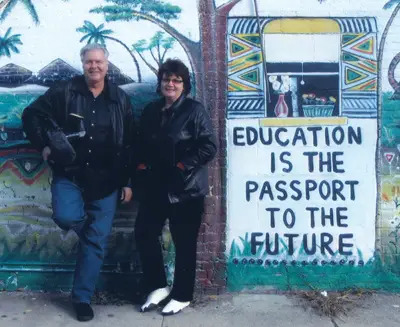

We sat down with Academy Award-winning filmmakers Alan and Susan Raymond to talk about their new documentary, Journey into Dyslexia, which debuts May 11 at 8pm on HBO2. The film examines the misconceptions of dyslexia and debunks the myths associated with the learning disability. Among those myths is the belief that dyslexia is a form of mental retardation – something 80 percent of Americans believe. “That is still the most alarming statistic for me,” says Susan Raymond. “I think nobody knows what dyslexia is. I think it’s a mystery to most people.”

Successful dyslexic adults, including consumer advocate Erin Brockovich, Nobel Laureate Dr. Carol Greider, and micro sculptor Willard Wigan, appear in the film to discuss their past struggles and how they have come to embrace dyslexia as a unique gift.

What was your inspiration for making this film, and what purpose do you hope it will serve?

Susan: I thought it was time for people to start talking about learning disabilities. One out of 10 people in America have a learning disability, which is a huge number. Dyslexia is a hidden disability, and it would be nice for people to understand what it is.

Alan: I think there is a general lack of information about the subject. Dyslexia accounts for 80 percent of all learning disabilities, yet the general public is not knowledgeable about dyslexia and there is a great deal of misunderstanding. Many people mistake it for other things, like mental illness, which it is not. We need to educate people.

What did you learn during filming?

Susan: When I was interviewing the adults, I was surprised to learn how they all struggled horribly in school. Even though they are now very accomplished and successful within their careers, memories of childhood humiliation or mistreatment are still fresh in their minds.

Did you find any other commonalities among these people?

Susan: They usually have an unusual strength. Thirty-five percent of entrepreneurs are dyslexic. They often discover what their interests are and create their own businesses around that.

Alan: The way they think is different from the conventional left hemispheric way of thinking. They tend to be more creative or visionary. Dyslexic people can see things that are atypical in a variety of disciplines, such as art, architecture, and science.

World-acclaimed micro sculptor Willard Wigan mentioned how one of his past teachers announced to the class, “Willard is a failure,” when he couldn’t write his name on the blackboard. Do you believe the treatment of students with dyslexia and other learning disabilities has gotten better over time?

Susan: According to a Roper poll, 80 percent of teachers believe that students with learning disabilities are as smart as typical students, 80 percent of teachers believe they know how to teach students with dyslexia, and 80 percent of teachers think dyslexia is mental retardation. Teachers think they know what they are doing when they certainly don’t.

Alan: When others see dyslexics or other students with disabilities as different, that can create issues. They taunt them and bully them because they “are not normal like me.” There is a full range of secondary emotional consequences that can arise, but it starts with the teacher humiliating the child. We interviewed well over 100 children, and none of them suggested that it has gotten better.

In the film you address the fact that reading, a task that dyslexics struggle with, is not a natural act and represents only one type of intelligence. How can we change the perception that reading proficiency equals intelligence?

In the film you address the fact that reading, a task that dyslexics struggle with, is not a natural act and represents only one type of intelligence. How can we change the perception that reading proficiency equals intelligence?

Susan: I think we take reading for granted. It’s a very complex process where the brain takes symbols and turns them around and changes them into words. It is a very sophisticated process, and it’s not easy to learn.

Alan: I think people have to accept the concept of human diversity and that there are different forms of intelligence. Not all of us are born alike. We shouldn’t all fit into one cookie-cutter definition in life.

Dr. Carol Greider, 2009 Nobel Laureate in physiology and medicine, mentioned in the film that she had always struggled with performing well on standardized exams. Do you believe that standardized exams are a fair assessment of a person’s intelligence and abilities?

Susan: I don’t think standardized tests really measure the ability of a person. People with dyslexia use the right side of their brains, so it takes them five times longer to do a task. That’s why students in school are eligible for extended time when taking tests. There was a study that showed if a dyslexic student was given extended time, there was a good chance that they could increase their score by about 50 percent. If you were to give a typical student extended time, their score will most likely only improve by 5 percent. They just need more time to process information.

We’ve really become a country of testers now. Dr. Greider was not a good test taker. She applied to 13 colleges and 11 of them only looked at those test scores and said,

“Well, forget her,” and two of the colleges looked at her other talents and realized that she was an interesting person and accepted her. We have to reevaluate what is “normal,” because we are going to miss out on so many talented people.

About half of students with learning disabilities eventually drop out of high school. What are some ways to help retain students with dyslexia and other learning disabilities in the school system?

Susan: Early identification is important. Identify and screen your child in kindergarten and certainly no later than first grade to see if they are struggling with reading. If you identify it early and put them in learning programs, that child will start reading as well as normal children by the third grade.

Alan: Also, I think children in special education give up on themselves because they feel there is no future in their academic studies. They should put students with learning disabilities into regular classes and integrate an inclusionary model into the system.

For more information and resources, check out: