Before our family trip to Kenya, I insisted on the vaccinations. Typhoid, hepatitis A, MMR, polio. I even drove the kids upstate to a clinic because the yellow fever vaccine was in short supply. Their arms hurt for days. For malaria we had to take pills, which for a 7-year-old and a 9-year-old is virtually impossible. I sprayed our clothes with Deet and packed the extra anti-malaria pills along with six bottles of Off and a scarf that was supposed to repel mosquitoes. My husband thought I was crazy. “Bobby says it’s not necessary,” he said. Bobby is our friend who lives in Kenya. We were on our way to visit him for what was going to be—to use a cliched phrase that we found ourselves reluctantly repeating—the trip of a lifetime.

“Why take a risk?” I argued.

“Whatever you want,” my husband said.

Finally, we were ready for what I thought was going to be the hardest part of our journey: a 17-hour plane ride. Instead, we breezed through the epic flight. “See?” My husband said. “It’s easy.”

Bobby was there to greet us and drove us through the packed, dusty Nairobi streets to his home behind a guarded gate. That afternoon, the kids held mini bananas while monkeys jumped on their backs. We fed giraffes and drank wine beneath avocado trees.

After three days, we flew to the Mara—the bush—where we watched a lioness kill a gazelle then offer the carcass to her cubs. We saw wildebeests, led by zebras, cross a river filled with crocodiles. Our kids gaped in awe from the back of the jeep and slept beneath mosquito nets back at camp.

Then we hopped another plane to Watamu, a small town on the Indian Ocean where we found ourselves in a beachfront five-bedroom with a personal chef. I read an entire novel while the kids frolicked in the pool. I am happy, I emailed a friend.

After snorkeling, we decided to check out the Crab Shack on the mangrove where we could watch a stunning sunset. It was 5pm, daylight just starting to fade. “Boys get your shoes,” I said.

A few seconds later we heard a shatter like a planter had been knocked over and then I saw what had actually happened, a vision that still haunts me every time I close my eyes.

Mack, my 7-year-old, who was running to get his shoes, had smashed right through the sliding glass door. Glass was everywhere and Mack was screaming. And then there was blood. So much of it. I thought of the gazelle in the Mara. I thought of the book I read where a boy walks through glass and dies. And I thought, is this it?

I immediately started reassuring everyone, but for the first time as a parent, I thought: It’s not going to be okay. This is when the good times end.

And then: What if? What if he had not left his shoes outside? What if we had decided to stay in that evening?

My hands shook as I wrapped Mack’s wounds. The ambulance arrived. A doctor tried to give Mack an IV, but his veins had collapsed.

We drove 2 hours through black night under pouring rain on dirt roads to a hospital where a young African girl was wheezing. Was this really happening?

There were waves of nausea and blurry floors. Finally, the doctor said, “He’s going to be okay.”

“He is?” I asked, still unsure.

We spent the rest of our vacation in African hospitals, getting Mack sewn back together. The pain was so bad at times that he needed IVs and shots and nerve-blockers. He screamed and cried and vomited from the medicine. But after a week, we learned there would be no permanent damage, minus a few brutal scars.

When we got home, there were notes and flowers from our friends. Exhausted, I unpacked our dusty clothes and saw the bottle of anti-malaria pills. I thought of all the shots I had made the boys get, the forms I carried with us in a sturdy plastic folder—proof of our exceptional health and fortitude. That was us before, I thought, before we knew what it felt like to see our tiny, precious child hurt so badly that time stops.

I threw the pill bottle in the trash. We had shielded ourselves against deadly, crippling diseases, and yet life had thrown us a curveball that no vaccine could have blocked.

Are we better for it? Who knows? But two months later, as I write this, Mack is kicking a soccer ball against the house, shaking the walls—something I’ve told him many times not to do. And I am grateful, so grateful for it.

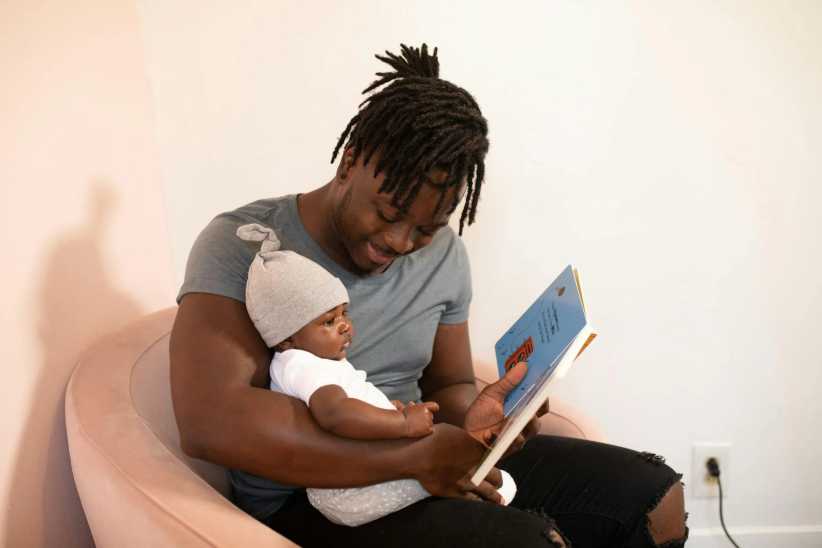

Main Image: Nate and Mack, the author’s sons, in the Mara with a Masai guide. Courtesy Shana Liebman