A learning disability diagnosis can usher in a challenging time for your family. But understanding the law and what your child is entitled to can spell success for the future.

A learning disability (shorthand: LD) is a neurological disorder that affects a child’s ability to process, store, analyze, and retrieve information. Approximately 2.9 percent of school-aged children in the United States are classified as learning disabled and receive special education services.

A learning disability (shorthand: LD) is a neurological disorder that affects a child’s ability to process, store, analyze, and retrieve information. Approximately 2.9 percent of school-aged children in the United States are classified as learning disabled and receive special education services.

Learning disabilities can show up in virtually every area of academics: “In math, reading, listening, organization, formulating language and response, and comprehension. It’s a complicated set of disabilities, all of which fall under the learning disability umbrella,” says Dr. Sheldon Horowitz, director of learning disability resources and essential information at the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

The most prevalent of the learning disabilities is found in reading. Some children are able to sound out words and read but struggle with comprehension. Others can read and understand but struggle with speed and automaticity. Many children also have co-occurring disorders such as autism or ADD/ADHD, a disorder that is commonly confused with learning disabilities. “Kids with learning disabilities and kids with ADD/ADHD often look very much the same because of the way they process, store, analyze, and retrieve information,” Dr. Horowitz says. And it’s important to recognize that the approaches to treating these special needs are different – and don’t have any impact on children with LD.

Diagnosis: LD

Emotions can run high when children are diagnosed with a learning disability. Children may feel lonely and isolated from their peers because they have to go to special classes or because they don’t fit in. And parents often feel scared as they wonder, “Is my child stupid or lazy?” Feelings of loneliness, frustration, and anger are common, says Ben Foss, director of access technology in the Digital Health Group at Intel and president of Headstrong Nation, a nonprofit organization, but it’s important to recognize that children’s difficulties don’t make them stupid.

“They have developmental disabilities that inhibit certain functionality, but they also have great creativity and strengths,” says Foss, who recommends that educators and parents play to those strengths. Encourage kids to embrace themselves for who they are – and reiterate that LD isn’t the only thing about them. A dyslexic himself, Foss knows firsthand what a learning disabled child feels. While in college, Foss (who now holds a J.D./M.B.A. from Stanford University) would fax his term papers to his mother so she could read them to him over the phone.

Dealing with LD is a group effort. Parental support is critical, but so too is having a qualified teacher – one, moreover, with the school behind him or her. When certain methods haven’t worked for your child, parents and the school together decide to pursue the special education referral process.

“The most important thing for a child, a parent, and a teacher to work on is for the child to articulate the nature of his or her learning disability,” Horowitz says. By becoming their own advocate, children can bridge the gap that sometimes exists between teachers and parents.

It’s the Law

The Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), formalized in 1975, with amendments made within the last seven years, states that children who have special learning needs are entitled to a “free and appropriate education” (FAPE) in the “least restrictive environment (LRE).” In essence, children diagnosed with LD are entitled to special education services provided by the school district, free of charge, and they cannot be segregated from their general education peers. If however, a child cannot be served in the general education setting, the school district is then obligated to find an appropriate setting at no cost.

Although federal law is clear that each state must provide services and support for children with LD, the ways in which these are implemented depend on the state education mandate, by regulations within the state, and by local practices at the county and school district level.

“These are individual decisions that are made on how educational practices are implemented within the federal guidelines,” Horowitz says. And with all the budget cuts school districts are facing, the ways in which services are provided may vary. Although schools are being forced to consolidate services to different groups of kids or to utilize faculty in different ways, they must adhere to IDEA. “There is no loophole for not providing services to kids with special needs,” Horowitz says.

First Steps

Your child should be formally evaluated by a licensed learning specialist or clinical psychologist provided free of charge by the school. If you’re not satisfied with the timeliness of the evaluation, or you wish to pursue a private evaluation, the costs can range anywhere from $1,000 to $5,000, although insurance may cover it.

After the evaluation, you will have the opportunity to attend the Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meeting and discuss the services the school is recommending. Do your research and come prepared with information and recommendations you believe are appropriate for your child. The IEP is a contract, and the most important document when appropriating services.

“The IEP stipulates that children receive a certain level of instruction at a certain intensity over a certain period of time and that progress be monitored so that [parents] know what is being offered is working,” Horowitz explains.

The IEP may stipulate that services be rendered in the general education classroom with special support brought in, in a general education setting where the child is moved to a separate space for part of the day, or that the child is moved to a completely different school or home-schooled. “The key is ‘appropriate.’ Is what the child is receiving appropriate, and is the child benefiting from that special education service?” Horowitz says.

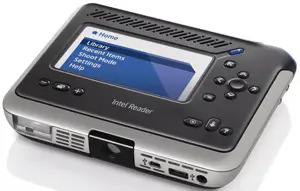

Accommodations, unlike modifications, don’t change what is expected from a child. “These are intelligent kids who have alternate paths to conquering, understanding, and mastering information,” Horowitz says. Accommodations may include extended time and alternate test settings; a date book or assistive technology for organization; a note taker; special classroom seating or lighting; typed, double spaced, or large-print handouts; or an alternative keyboard for those with motor challenges. Audio books from organizations like Bookshare® or Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic® and assistive technologies like e-readers, high-speed flatbed scanners, and the Intel Reader (pictured at right) can help students who struggle with reading and comprehension and may be provided free of charge if it’s included in the IEP and budgets allow.

Accommodations, unlike modifications, don’t change what is expected from a child. “These are intelligent kids who have alternate paths to conquering, understanding, and mastering information,” Horowitz says. Accommodations may include extended time and alternate test settings; a date book or assistive technology for organization; a note taker; special classroom seating or lighting; typed, double spaced, or large-print handouts; or an alternative keyboard for those with motor challenges. Audio books from organizations like Bookshare® or Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic® and assistive technologies like e-readers, high-speed flatbed scanners, and the Intel Reader (pictured at right) can help students who struggle with reading and comprehension and may be provided free of charge if it’s included in the IEP and budgets allow.

Parents as Partners

It’s important not to feel pressured to sign anything until you understand exactly what the IEP states and how the recommended services will be implemented. If the IEP is signed and you learn about a new technology that you believe can help your child, for example, you can ask to hold another meeting to revise the IEP.

“There are absolutely ways for this living, breathing document – which is not written in stone and needs to be reviewed on a regular basis throughout the school year – to be amended and updated in ways that are meaningful for the parent and the school,” Horowitz says.

These due process rights are articulated at the time you enter the evaluation process, not at the IEP meeting, and all attempts for recourse should be well documented.

Sometimes when parents are not satisfied with the IEP, mediation will take place with a professional mediator, a parent advocate, or even an attorney. Horowitz warns parents not to go into an IEP meeting wanting to do battle; instead, take a ‘parents as partners’ approach. “When parents and schools finally sit down and talk, they realize that they’re both interested in the same thing, and they can put together a plan that really does work.”

Other Impairments

For some children who have physical or mental impairments that impact their learning time, yet are not eligible for special education services, the 504 plan, or section 504 of the Rehabil-itation Act of 1973, can provide services for them. This civil rights law prohibits discrimination against children with disabilities and states that the school must provide accommodations so the student can participate in the general education setting. The evaluation and process for receiving these services is different from the process for pursuing special education services. Visit www.nymetroparents.com/504comparison for a chart detailing how 504 and IDEA work with each other and complement one another, so you as the parent can better assist your child’s educational team in ensuring your child’s right to a free and appropriate education.

Also see: Learning Disabilities: Definitions and Symptoms

A Parents’ Guide to Special Needs