Insideschools, which provides authoritative, independent information about New York City public schools, shares the questions to ask about your child’s math and science education.

Students harvest crops from schoolyard planters, an activity that may be the result of science partnerships a school has undertaken to complement traditional classroom learning.

This is a good time to be informed about your child’s math and science education in pre-kindergarten through fifth grade. It’s a time of change. Many schools are grappling with the best way to help kids meet goals in the Common Core State Standards. There is a national conversation about why our teens lag in math and science internationally. Meanwhile, the early years are important. A child’s ability with numbers in the earliest grades predicts math prowess in the older grades.

In our first installment of the Parents’ Guide to Math & Science, “A Parents’ Guide to Quality Math and Science Education,” we discussed what things to look out for in your kids’ classrooms to help you evaluate the strength of the school’s math and science programming. In this part, we help you ask the right questions at home and at school. No school is perfect, but if you understand the strengths and weaknesses of your child’s place of learning you can help fill in the gaps—even if you don’t know much about math and science yourself.

Questions to Ask the Teacher

Obviously, you want to ask questions as part of friendly curiosity, not grilling the teacher. Remember, you both have your children’s best interest at heart. Here are some ideas for questions:

How do you challenge the best students and help struggling learners?

Reaching children of different abilities in the same class is one of a teacher’s most difficult tasks, particularly when it comes to math. Most teachers know how to find books to match a child’s reading level, but they often pitch math lessons to the whole group in order to cover a certain amount of material.

The best schools ensure the brightest children can move ahead of their peers, either by working on more complex problems or by working independently on math websites such as Khan Academy. They also ensure struggling kids get the help they need, often in small groups inside or outside the classroom.

Faster learners shouldn’t be told to read a book while other children finish their work. They should be working on math during math time. It’s okay if a teacher occasionally asks them to double-check their work or to help their peers, but faster learners need a chance to do more advanced work.

At PS 172 in Brooklyn, we sat in on a fifth grade math class in which the teacher managed to adapt the same complex problem for different children: If two teachers, shopping together, each buy a pair of shoes at a “buy one, get one for half-price” sale, what’s the fairest way to divide the cost? Some children worked on the problem independently or in pairs, others got little hints from the teacher, and still others got step-by-step instructions from the second teacher in the class, who is trained in special education. At the end of the period, all children sat on a rug and discussed how they arrived at the answer.

|

Most local schools hold parent-teacher conferences in November. Take advantage of the brief time you have to connect on matters that, well, really matter. |

Does the school do anything to encourage girls in math?

Girls often get discouraged by math early in their school careers. Good schools work to bolster girls’ confidence and break down stereotypes about girls not liking math. These schools encourage girls to build with blocks and Legos, join the math or robotics club, and hang out in the computer lab with the technology teacher during lunch. Mentors count: Girls often model their behavior after their female teachers. It’s particularly important for female teachers not to say “I wasn’t good at math.” Research shows female teachers often unwittingly pass on their own insecurity about math to their female pupils.

Do you have any math and science partnerships?

Some schools hire consultants to train teachers in challenging math curricula such as Math in Focus, based on math programs in Singapore. Many schools have partnerships with colleges, museums, or established science programs.

Children in grades second through fourth learn environmental awareness and about preservation of bird habitats as part of an Audubon Society’s program called “For the Birds!” Similarly, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology distributes grants to teachers and assists youngsters in high-quality data collection about birds in urban areas.

In a project called Tomatosphere, children at PS 205 in Queens grow tomato seeds in conditions designed to simulate those on a trip to Mars. They contribute data to the Canadian Space Agency’s project studying the feasibility of growing edible plants on long journeys in space.

The Center for Architecture Foundation helps children at PS 42, PS 199 and other schools build models such as a long house, a tenement building, and a skyscraper to show New York City’s history and development through 200 years of architecture.

Are there ways for students to get involved with math and science outside the regular school day?

Schools that have a strong math and science focus often have robotics, math, or chess clubs during lunch or after school. Children involved in some of these programs may even take part in national competitions.

How much time is spent on test prep?

The best schools don’t make a major production of math and science tests. In strong schools teachers spend a little time each day about one or two months prior to the tests getting kids used to the format, but most learning is part of a well thought-out plan of regular lessons throughout the school year. Children are tested in math every year, beginning in third grade. Children are only tested in science in the fourth grade. Something to watch out for: After years of no science, kids suddenly get four days a week of science in the fourth grade—so the school looks good on a test.

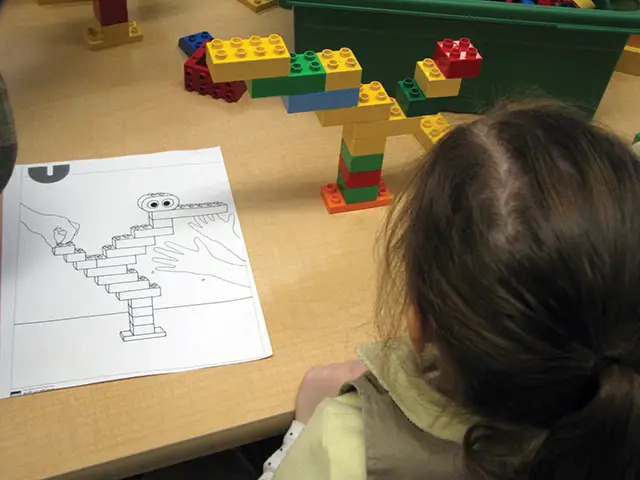

A girl at PS 185 The Early Childhood Discovery and Design Magnet in Manhattan looks at plans to help her build a Lego design. Girls often need to be encouraged to work through the tricky parts of a science challenge—and that support is tantamount in today’s world; minority women comprise fewer than 1 in 10 employed scientists and engineers.

What Does Your Child Say?

Another telling clue to successful STEM education: Is your child talking about math and science? Does she bring her enthusiasm home?

One mother we spoke to as part of our research said that her son was thrilled to tell her what he learned about migration when he tallied the number of pigeons in his neighborhood over time as part of a project at the Brooklyn New School. First-graders at Midtown West in Manhattan ask their parents to help them find simple machines at home—a flip-top lid (a.k.a., a lever) and a doorstop (for scientific purposes, a wedge).

Does your child use words such as “carnivore,” “porous,” “sediment,” “volcanic ash,” or “metamorphosis”? Good science instruction builds a child’s vocabulary.

It’s a good sign if kids are thinking about math and not just doing it, according to Mark Saul, Ph.D., director of the Center for Mathematical Talent at New York University. Can your child use a measuring cup to double a recipe while cooking with you? Or figure out how long it will take for Grandma and Grandpa to arrive by looking at the clock and doing the math? How about determine approximate mileage for a family trip by looking at a map? Those are all good signs.

Don’t worry too much if you find your children’s homework confusing—many parents do. And don’t force them to do math the way you did, Dr. Saul says. Instead, be curious about the way your kids are doing it. Ask them questions; don’t dole out answers. Acknowledge them for trying hard and not giving up. Research shows persistence is what counts in the long run—not getting everything right the first time.

If your children are engaged and show curiosity themselves, things are probably okay. If they avoid homework or race through it—if they are bored, anxious, or confused—there may be a problem.

Some schools send home different homework packets depending on a child’s ability. Teachers at PS 59 in Manhattan send home a customized plan for each child including reading levels and math strengths, with games kids and parents may play together to support math concepts and skills they’ve studied in school. They send home pictures of math strategy charts used in class so parents can also reference them at home, and post ideas on a web page.

The specifics of what your child talks about will vary based on his classroom experiences, but rest assured, if he’s engaged and truly learning math and science, he’ll likely be enthusiastic about what he shares.

Clara Hemphill, founder and senior editor of Insideschools, is the author of New York City’s Best Public Elementary Schools: A Parents’ Guide. Lydie Raschka, a writer at Insideschools, is a former public school teacher and a graduate of Bank Street College. Insideschools.org is a project of the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School.

For what to look for in your child’s classroom—from evidence of multiple approaches to instilling math concepts to the types of toys that serve as effective teaching tools for younger kids—read part one of this series.

Also see:

Maker Faires in the New York Metro Area