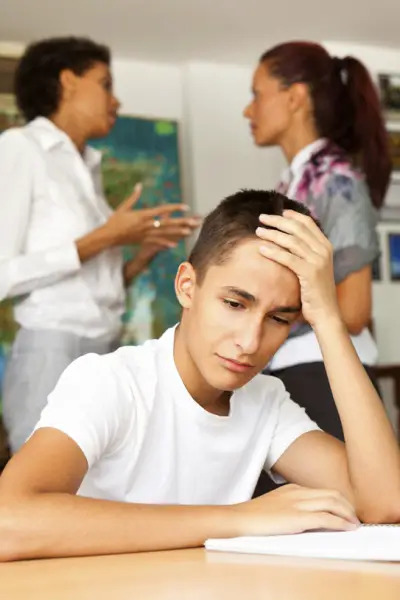

How can you help your child with a psychiatric or learning disability deal with going back to school? Model confidence, create structure, and get to know the new teacher. Our expert offers six things to keep in mind as the academic year kicks into swing.

Every child faces challenges when heading back to school. But back-to-school time can be exceptionally difficult for the 20 percent of children who suffer from a psychiatric or learning disorder. The school environment demands many things that summer activities don’t—the ability to sit still, get organized, stay on task, and adapt to a new, highly structured daily schedule. School also requires kids to separate from their parents and interact with peers—enormously challenging tasks for any child with anxiety.

Here are six things parents need to know about starting school with vulnerable children:

1. Psychiatric health problems emerge at back-to-school time.

Children with special needs require a lot of help learning how to manage a new schedule. As a parent, you can ease your child’s anxiety by modeling confidence and calm behavior, and by imposing structure in family life (mealtime, homework, and bedtime routines). But if your child shows signs of extreme anxiety and has unusual difficulties in school, you should immediately discuss your concerns with your child’s teacher as well as a mental health professional, someone who can advise on whether a child’s problems are normal and age-appropriate or require further evaluation.

2. Kids’ brains are changing dramatically.

Profound changes occur in the brains of children, particularly as they enter their teens. The teen brain starts “pruning”—strengthening some synapses and eliminating many others. A temporary imbalance of this pruning in certain areas of the brain has been linked to teens’ erratic and risky behaviors, as well as to the onset of anxiety disorders, depression, and substance abuse. It’s important to keep communication open at this vulnerable time, when teenagers are starting to look like adults, and think they are adults, but may not have the skills to manage stress. If you haven’t already started setting time aside each day to talk to your child about challenges and new experiences at school, now is the perfect moment.

3. Anxious parents send anxious kids to school.

Anxiety disorders run in families. Plus, anxious people tend to marry other anxious people; children with two anxious parents are at especially high risk. But genetics are just one factor. Environment is another. Kids really are like sponges, absorbing the energy and adopting the behaviors around them. One of the most helpful things you can do is model calm, confident behavior, particularly while helping a child get ready for school. A child usually starts school no calmer than her least-relaxed parent.

4. Teachers matter, maybe even more than you think.

Teachers get to know a child’s family through the child’s eyes, and they get to know how a child behaves without his parent present. This means parents can get all kinds of information about a child from his teacher—information about learning difficulties and peer problems as well as academic achievements and close friendships. Teachers are allies, and you should talk to them regularly. Good questions to ask include: How is my child doing? Do you have any concerns about his social or academic skills? Do you think he needs my help with anything?

5. Homework time is crucial.

Young children with learning difficulties, as well as those without any documented problems, can benefit from their parents’ involvement during homework time. Parents should set aside time for a structured “homework session” each evening. A good routine might start like this: Create space on a desk to work; help him clean out his backpack; review the day’s assignments; and discuss the homework as well as any questions about it. You can observe your child’s learning strengths and weaknesses this way while also reinforcing good study habits. Be positive and encouraging.

6. Don’t jump to conclusions.

Kids grow and develop at different rates. Ideally, a child will acquire various skills within expected time periods, but she may develop more quickly in one area than another. Parents often worry when, for example, one 5-year-old can read fluently while another can barely sound out words on the page. But a lag in one area of development doesn’t mean a child has a disorder. If you think there might be a problem with your child’s development, talk to her teacher. A seasoned teacher, with about 10 years of experience, can frame your child’s progress in relation to as many as 300 other kids. Good teachers are invaluable allies.

Additionally: Did you know your stress can negatively impact your child? Learn how to control your stress so your family as a whole can be healthier.

Harold S. Koplewicz, M.D., the founding president of the Child Mind Institute in Manhattan, is one of the nation’s leading child and adolescent psychiatrists. He is widely recognized as an innovator in the field, a strong advocate for child mental health, and a master clinician. Dr. Koplewicz founded the NYU Child Study Center in 1997 and served as its director for 12 years. Since 1997 he has been the editor-in-chief of the “Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology.” A frequent TV guest, his most recent book is “More Than Moody: Recognizing and Treating Adolescent Depression.”

The Child Mind Institute is an NYC-based nonprofit organization dedicated to transforming mental health care for children everywhere. Visit childmind.org for a wealth of information related to your child with special needs, including strategies for dealing with diagnosis and behavior, symptoms and signs, practical tools, videos, and more.