When my daughter Rachel was four, she decided she would wear only dresses to preschool. Before long, her favorite activity became polishing her nails and applying pretend lipstick. As a proud feminist, I was flabbergasted. Where, I wondered, was this behavior coming from?

When my daughter Rachel was four, she decided she would wear only dresses to preschool. Before long, her favorite activity became polishing her nails and applying pretend lipstick. As a proud feminist, I was flabbergasted. Where, I wondered, was this behavior coming from?

As it turns out, Rachel was acting on a host of messages—some subtle, some not so subtle—that she’d been receiving since birth. “Research shows that infants can tell the difference between males and females as early as their first year,” says Elaine Blakemore, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Indiana University Purdue University, in Fort Wayne. What’s more, they begin forming gender stereotypes almost as soon as they know they are boys or girls.

Gary Levy, Ph.D., director of the Infant Development Center at the University of Wyoming, in Laramie, studied 10-month-olds to see if they could comprehend gender-related information. “We showed the babies videos of certain objects paired with either a male or a female face,” he says. “The children became accustomed to seeing certain objects with a man’s face and others with a woman’s face, and they recognized when we violated this pattern.”

It’s not until kids are three or four, however, that they really begin to work out for themselves what it means to be a boy or a girl. As they gradually test their theories through observation and imitation, many preschoolers begin adopting stereotypical behaviors. Girls, for example, may spend most of their time in the dress-up or kitchen corner of their preschool classroom. Little boys may engage in activities that make them feel powerful, such as constructing block towers and then knocking them down with a toy truck.

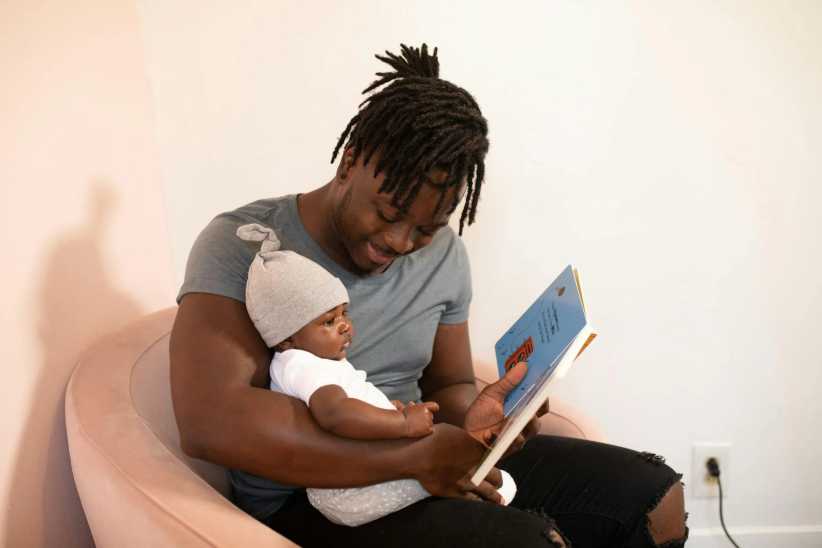

Although many progressive parents, like me, are shocked to see their children conforming to such narrowly defined gender play roles, we may inadvertently perpetuate those stereotypes. “Adults aren’t aware of how much they reinforce stereotyping by complimenting boys and girls in stereotypical ways—commenting on how pretty a little girl looks in her dress, for example,” says Diane Ruble, Ph.D., director of the Child Studies Program at New York University. “And even the most enlightened fathers often become uncomfortable when they see their sons playing with dolls or exhibiting other traditional feminine behavior. One three-year-old boy I know liked wearing his hair in a ponytail. But one day, when his mom asked if he wanted her to fix his hair in a ponytail, he replied, ‘No—Daddy would be mad!’ ”

Preschoolers also pick up gender clues from older siblings, teachers, and, perhaps most insidiously, the media. “The action figures for boys advertised on TV and seen in TV shows almost invariably have big muscles and are depicted as powerful and active,” says Diane Levin, Ph.D., a professor of education at Wheelock College, in Boston, and author of Remote Control Childhood? Combating the Hazards of Media Culture (NAEYC). “The dolls marketed to girls are pretty, sweet, and sexy. Preschoolers are drawn to these extremes.”

Michelle Graves, a consultant with High/Scope, an educational-research foundation in Ypsilanti, Michigan, witnessed such behavior firsthand during classroom observation. After playing in a housekeeping area, boys would deny having done so, when asked.

According to some experts, it’s not unusual for preschool girls to go through a pink and frilly phase and for preschool boys to spend their days imitating superheroes. In this culture, these phases pass. Nevertheless, it’s important for parents to guide their preschoolers’ thinking to make sure that they don’t end up with lasting gender ideas based on stereotypes. Here are a few suggestions:

Encourage mixed-gender playdates, and expand the range of activities for each gender.

Boys and girls who play together tend to engage in more varied activities. When they’re playing with children of the opposite sex, boys may be more likely to participate in creative make-believe games or to practice their fine motor skills with art projects. Girls who regularly play with boys may spend more time outdoors, building their bodies through vigorous exercise.

Reinforce behaviors that shatter stereotypes.

Rather than rule out certain stereotypical behaviors, make a point of reinforcing those that challenge the stereotype. For example, you might tell your daughter, “I love to see you in the sandbox” or “Wearing pants today was a good idea—it’ll be so much easier to climb the monkey bars.” A father may tell a son in tears, “Sometimes I feel like crying too.”

Question all generalizations.

Encourage your child to deal with other kids as individuals in specific situations rather than as representatives of their gender. “If, for example, your son comes home complaining, ‘Girls are so stupid!’ try saying something like ‘It sounds like you’re angry at someone. Who are you angry at?’” Dr. Levin suggests.

Janice Garfinkel, a teacher in South Bellmore, constantly tries to probe generalizations in her classroom. “In preschool, the girls tell the boys, ‘Pretend you’re the dad and it’s time for you to come home from work. I’m the mom and I’m taking care of the baby.’ I always ask the kids, ‘Do you know any moms who go out to work each day?’”

Tune in to your own biases.

Moms and dads themselves, of course, may be clinging to outmoded stereotypes, in both their thinking and their actions. “Parents should review their behavior to make sure they’re not doing or saying anything that feeds into something harmful,” says Charles Flatter, Ph.D., a professor of human development at the University of Maryland, in College Park. “Boys and girls both need to be shown that there are alternatives to the classic stereotypes.”

Barbara Solomon Josselsohn is a Westchester-based freelance writer specializing in home and family topics. Her work has appeared in “American Baby,” “The New York Times,” and “Westchester Home Magazine.” This article originally appeared in “Parents” magazine.

If you loved this article, check out these related articles from NYMetroParents:

Books that Teach Children About Diversity and Tolerance

The Long-Term Benefits of Sports for Girls